Wong Cheeping, 1860s-?

Contents: English | 漢語 | Français | Sources 來源 | Images 圖片 | Notes 腳註

English

Mr. Wong Cheeping: Business Man, Community Member, Transnational Figure

Business Man - Community Member - Transnational Figure

by Amanda Law

Described as a “well-to-do, well dressed individual” (“Girl Slave”), in Edith Eaton’s journalism, Mr. Cheeping, or Wong Cheeping (黃志平)1, was an established businessman and a respected member of the Chinese community in 1890s Montreal. Eaton describes him as fairly fluent in English, well informed, and well mannered (“Girl Slave”), and she gestures to a grocery business he was planning to open. In 1894, with five business partners, Lou Chan Hoy (盧燦開), Wong Chun (黃昌), Lou Sum (盧深), Chan Man (陳晚), and Lee Jian (李見) (“Sociétés et Dissolutions”), Cheeping opened the Tye Loy (泰萊) Company, a vendor of Chinese and Japanese goods, at 82 Bleury Street (Lovell’s 1894-95 40). It likely attracted Asian customers seeking familiar tastes and smells from home as well as non-Asian customers interested in “exotic” and unfamiliar goods and products. Chinese laundries saturated the Chinese business market in Montreal, but Tye Loy was one of only thirteen Chinese groceries established between 1893 and 1900 (Helly 92). In 1895, it was described as the most important of the six Chinese stores operating in Montreal at that time (“Chinese Colony”).

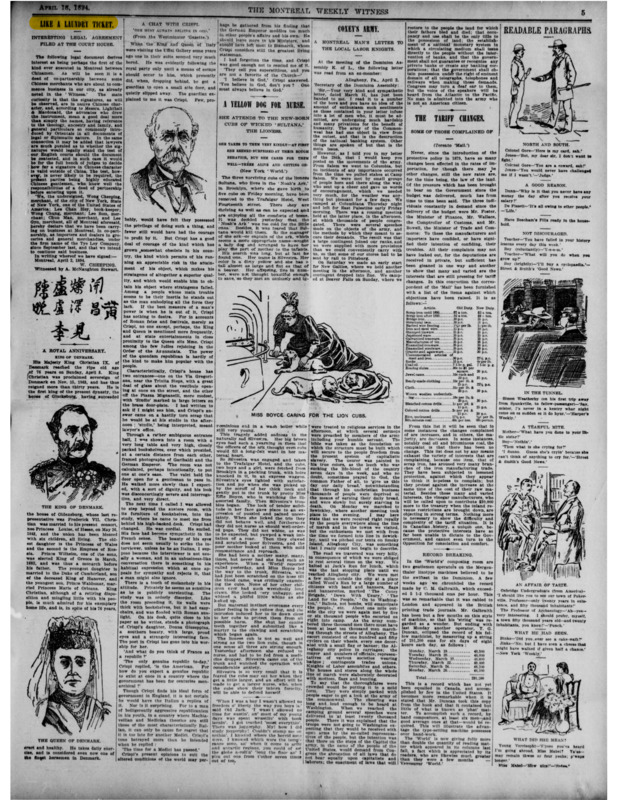

Cheeping was not only an established figure in Montreal’s Chinese business landscape; he was also an active member of the Chinese community in the Northeast. While he did not have a wife with him in Montreal, he had several local and transnational friends and associates. For example, when Li Sing, another Chinese merchant, stopped in Montreal on his way to New York after visiting China with his wife in 1895, Cheeping hosted the couple at his Bleury Street residence for three weeks (“Chinamen with German Wives”). This suggests that Cheeping had an expansive social network beyond Montreal and Guangzhou (Canton). He had established himself as a merchant in New York City as well, evidenced by his signing the agreement for the Tye Loy (泰萊) Company, as a “merchant of the city of New York” (“Laundry Ticket”).

While he learned English and adapted to Canadian manners, which Eaton praises in “Girl Slave in Montreal,” he also held on to Chinese customs and traditions, and shared his knowledge with people outside his community, imparting information about Chinese religions to curious reporters (“Chinese Religion”) or educating them on audience etiquette in Chinese theatres (“The Chinese and Christmas”), both of which Eaton features in her journalism for the Montreal Daily Star.

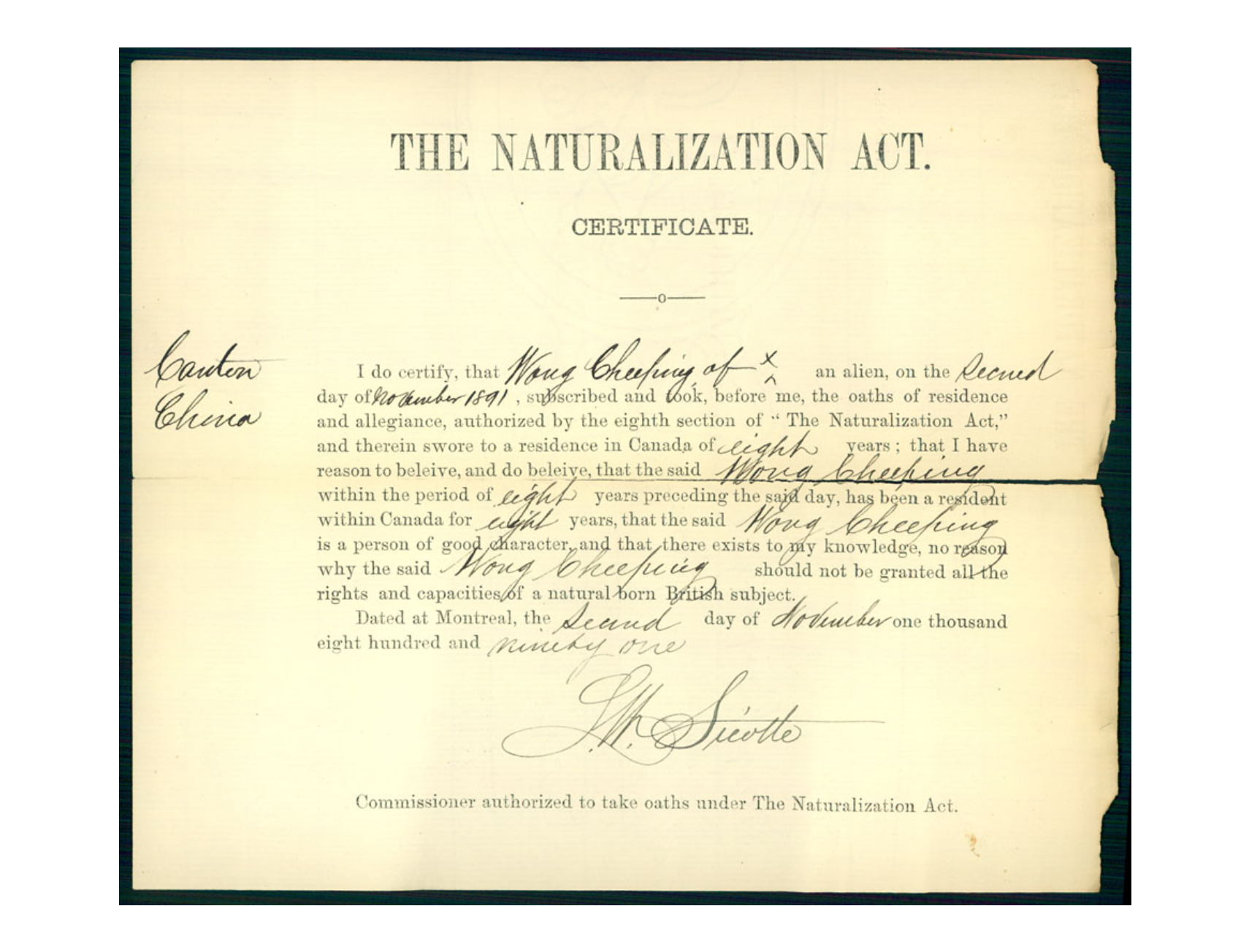

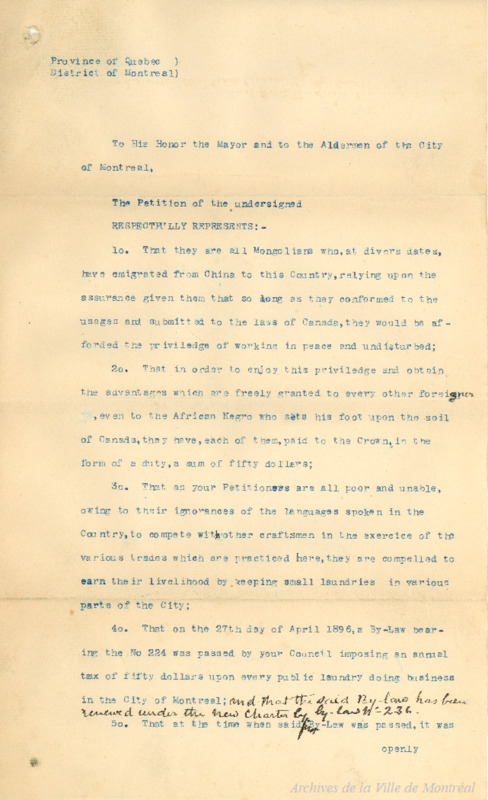

Cheeping was born in Canton (modern-day Guangzhou, China) and immigrated to Montreal in 1883 (Naturalization Documents). He was likely born before 1865, but there is sparse documentation accessible to us of his life outside of Canada. He lived in Montreal for eight years before applying for naturalization. Attaining citizenship was an especially difficult endeavour for immigrants such as Cheeping, considering the Canadian state and society’s discrimination against Chinese people, materialized in the 1885 Chinese Immigration Act which restricted Chinese immigration to Canada by imposing a $50 head tax on every Chinese person seeking entry. Having arrived in Canada two years before the implementation of the head tax, Cheeping avoided paying the fee. Even so, his application for citizenship coincided with the tax’s deployment, and the sentiment that undergirded it–a desire to keep Chinese people out of Canada–likely influenced the naturalization process for Cheeping. He was sworn in on November 2nd, 1891 (“Naturalized as British Subjects”) and received his official citizenship documents in January 1892.

There are few details about Cheeping’s years prior to his arrival in Montreal or the years in Montreal before his naturalization. His signature on the Tye Loy (泰萊) Company business agreement suggests that he lived in New York before or simultaneously with his residence in Montreal, but we have few sources of his presence in New York. Cheeping perhaps arrived in Canada having already established himself in the US as a merchant, an occupation that would later be exempt from the head tax, suggesting that the Canadian state sought to attract these individuals for their financial prospects. According to Eaton, Cheeping became fairly fluent in English and familiar with the social customs of Canada (“Girl Slave”) in the eight years before his naturalization, tasks that would be easier to accomplish if he were financially secure and did not have to worry about finding employment. Financial stability would have also granted him access to social circles that could teach him Canadian manners and customs. In addition, it would have allowed him to support his “bright and intelligent” (“Girl Slave”) sixteen-year-old cousin who attended school in Montreal.

In 1896, Cheeping travelled back to China in the company of Sin Chow Kee (沈洲紀) and Sin Kee (沈紀), two other merchants associated with the Tye Loy (泰萊) Company (“Briefs”). Whether or not he returned to Montreal after that trip is unknown. He handed the Tye Loy (泰萊) Company off to his business partner Lou Chan Hoy (盧燦開) (“Will Bring His Wife Here”), suggesting that his trip would be a lengthy, if not permanent, return to China to rejoin his wife. After that, traces of Cheeping’s presence in Montreal newspapers disappear. It is possible that he returned to Montreal, but it was never reported because he did not rejoin Tye Loy. Or perhaps he decided against returning, as the tax to bring his family to Canada would have been too steep. Perhaps he re-established himself in New York. Wherever Cheeping’s path led after 1896, his departure from Canada after undergoing the lengthy and arduous process of naturalization, coupled with his vague presence in New York, presents Cheeping as a transnational figure who traversed a complex path, of which Montreal was only a small piece of the larger story.

漢語

Mr. Wong Cheeping: 商人、社區成員、跨國人物

商人 - 社區成員 - 跨國人物

作家Amanda Law

在伊迪絲·伊頓(Edith Eaton,中文名也作水仙花) 的新聞報導中,志平(Cheeping)先生或 黃志平2(Wong Cheeping)被描述為“富裕、衣冠楚楚的人”(“蒙特利爾的女奴” / “Girl Slave“)。 他是 1890 年代蒙特利爾華人社區的知名商人和受人尊敬的成員。伊頓形容他英語相當流利、見多識廣、彬彬有禮(“蒙特利爾的女奴” / “Girl Slave“)。 她也提起了他打算開的一家雜貨店。 1894 年,黃志平與五個商業夥伴 , 盧燦開Lou Chan Hoy), 黃昌(Wong Chun), 盧深(Lou Sum), 陳晚(Chan Man),李見(Lee Jian)(“Sociétés et Dissolutions”), 一起在布魯里街82號(82 Bleury Street)開設了 泰來(Tye Loy)公司,一家中國和日本商品的供應商(Lovell’s 1894-95 40)。它或許吸引了尋求熟悉家鄉口味和氣味的亞洲顧客,以及對“異國情調”和不熟悉的商品和產品感興趣的非亞洲顧客。在蒙特利爾的華人業態中,洗衣店佔很大一部分,但泰來是 1893 年至 1900 年間建立的僅有的13 家華人雜貨店之一 (Helly 92)。 1895年,它被描述為當時在蒙特利爾經營的六家華人商店中最重要的一家(“華人殖民地”/“Chinese Colony”)。

黃志平不僅是蒙特利爾華人商業界的知名人物, 他還是加拿大東北部華人社區的活躍成員。他在蒙特利爾雖然沒有妻子,但是有幾個加國內外的朋友和同事。例如,當另一位中國商人李星(Li Sing)于1895 年與他的妻子訪問中國後,在前往紐約的途中在蒙特利爾停留時,黃志平在他位於布魯里街的住所接待了這對夫婦三個星期(“有德國妻子的中國人” / “Chinamen with German Wives”)。這表明黃志平擁有著超越蒙特利爾和廣州 (Canton) 的廣泛社交網絡。他也在紐約市確立了自己的商人地位,有他以“紐約市的商人”名義簽署泰來(Tye Loy)公司協議為證(“洗衣票”/“Laundry Ticket”)。

他在學習英語和適應加拿大禮儀的同時,他還堅持中國的習俗和傳統,並與社區外的人分享他的知識。伊頓在《蒙特利爾的女奴》中讚揚了這一點。他向好奇的記者傳授有關中國宗教的信息( “中國宗教”/“Chinese Religion“)或教育他們在中式劇院的觀眾禮儀(“中國人和聖誕節”/“The Chinese and Christmas“)。伊頓在她為蒙特利爾每日星報(Montreal Daily Star)撰寫的新聞報導中都提到了這兩個方面。

黄志平出生於廣東(現代中國廣州)。他在 1883 年移民到蒙特利爾(根據他的入籍文件)。他很可能出生於1865 年之前,但我們能接觸到關於他在加拿大以外生活的文件少之又少。在申請入籍之前,他在蒙特利爾居住了八年。如果我們考慮到加拿大國家和社會對中國人的歧視,獲得公民身份對於像黃志平這樣的移民來說尤其困難。這最明顯體現在 1885 年的華人移民法中。該法通過對每個尋求入境的華人徵收 50 美元的人頭稅來限制華人移民。 因為黃志平在人頭稅實施的兩年之前抵達加拿大,他避免了支付費用。即便如此,他申請公民身份的时机恰逢華人人頭稅啟徵,將中國人拒之門外的風氣甚囂塵上。這可能影響了黃志平的入籍過程。他於 1891 年 11 月 2 日宣誓入籍(“歸化為英國臣民”/ “Naturalized as British Subjects”),並於 1892 年 1 月收到正式的公民身份文件。

關於黃志平抵達蒙特利爾之前的歲月,或入籍之前在蒙特利爾的歲月,幾乎沒有詳細信息記載。他在 泰來(Tye Loy)公司商業協議上的簽名表明他有可能在紐約及蒙特利爾先後,或是同時,居住過。然而,我們幾乎沒有關於他在紐約的資料。 黃志平到達加拿大時可能已經在美國確立了自己的商人地位。這一職業後來免徵人頭稅。這表明加拿大政府是為了試圖吸引有這樣財務前景的人。

根據伊頓的記敘,黃志平在入籍前的八年裡,英語相當流利,也熟悉加拿大的社會風俗(“蒙特利爾的女奴” / “Girl Slave“)。當他在經濟上有保障,不用擔心找工作時,這些任務也更容易完成。穩定的財務狀況也能讓他能夠進入社交圈。 從而學到加拿大的禮儀和習俗。此外,這將使他能夠支持他在蒙特利爾上學的 16 歲“聰明伶俐”的表妹(“蒙特利爾的女奴” / “Girl Slave“)。

1896 年,黃志平在 沈洲紀 (Sin Chow Kee) 和 沈紀 (Sin Kee) 的陪伴下返回中國。 這兩家商人是與泰來公司(“Briefs”)有關聯。他在那次旅行後是否返回蒙特利爾不得而知。他將 泰來公司交給了他的商業夥伴 Lou Chan Hoy(“將把他的妻子接到這來”/“Will Bring His Wife Here”)。這暗示他返回中國與妻子團聚的旅程是長期, 甚至永久性的。此後,奇平存在的痕跡在蒙特利爾報紙上消失了。他或許回到了蒙特利爾,但從未被報導過,因為他沒有重新加入泰來。又或許,他可能決定不返回加拿大,因為將他的家人帶到加拿大的人頭稅太高了。也許他在紐約重新站穩了腳跟。無論黃志平在 1896 年之後走向何方,他在漫長而艱鉅的歸化過程後離開加拿大的經歷,再加上他在紐約的模糊存在,都將他呈現為一個穿越複雜路徑的跨國人物。而在黃志平整個人生故事當中,蒙特利爾只佔一小部分。

Français

M. Wong Cheeping: Homme d’affaires, membre de la communauté, figure transnationale

Homme d’Affaires - Membre de la Communauté - Personnage Transnational

Décrit comme un « individu aisé et bien habillé » (« Girl Slave »), dans les articles d’Edith Eaton, M. Cheeping, ou Wong Cheeping (黃志平)3, était un homme d’affaires établi et un membre respecté de la communauté chinoise dans les années 1890 à Montréal. Eaton le décrit comme parlant assez couramment l’anglais, bien informé et bien élevé ( « Girl Slave »), et elle fait allusion à une épicerie qu’il prévoyait d’ouvrir. En 1894, avec cinq associés, Lou Chan Hoy (盧燦開), Wong Chun (黃昌), Lou Sum (盧深), Chan Man (陳晚), et Lee Jian (李見) («Sociétés et Dissolutions» ), Cheeping ouvre la Tye Loy (泰萊) Company, une boutique de produits chinois et japonais, au 82 rue Bleury (Lovell’s 1894-95 40). Elle attirait probablement des clients asiatiques à la recherche de saveurs et d’odeurs familières ainsi que des clients non asiatiques intéressés par des biens et produits «exotiques» et inconnus. Les blanchisseries chinoises saturent le marché commercial chinois à Montréal, mais Tye Loy est l’une des treize seules épiceries chinoises établies entre 1893 et 1900 (Helly 92). En 1895, la boutique est décrite comme la plus importante des six épiceries chinoises en activité à Montréal à cette époque (« Chinese Colony »).

Wong Cheeping n’était pas seulement une figure établie dans le paysage commercial chinois de Montréal; il était également un membre actif de la communauté chinoise du Nord-Est. Bien qu’il n’ait pas de femme avec lui à Montréal, il avait plusieurs amis et associés locaux et transnationaux. Par exemple, lorsque Li Sing, un autre marchand chinois, s’arrête à Montréal en route pour New York après avoir visité la Chine avec sa femme en 1895, Cheeping héberge le couple dans sa résidence de la rue Bleury pendant trois semaines (« Chinamen with German Wives »). Cela suggère que Wong Cheeping avait un vaste réseau social au-delà de Montréal et de Guangzhou (Canton). Il s’était également établi comme marchand à New York, comme en témoigne sa signature de l’accord pour la Tye Loy Company, en tant que «marchand de la ville de New York» (« Laundry Ticket »).

Tout en apprenant l’anglais et en s’adaptant aux mœurs canadiennes, dont Eaton fait l’éloge dans « Girl Slave in Montreal », il conserve également les coutumes et traditions chinoises et partage ses connaissances avec des personnes extérieures à sa communauté, communiquant des informations sur les religions chinoises aux journalistes curieux ( « Chinese Religion ») ou les éduque sur l’étiquette du public dans les théâtres chinois (« The Chinese and Christmas »), deux sujets qu’ Eaton présente dans ses articles pour le Montreal Daily Star.

Wong Cheeping est né à Canton (aujourd’hui Guangzhou en Chine) et a immigré à Montréal en 1883 (documents de naturalisation). Il est probablement né avant 1865, mais nous disposons de peu de documentation sur sa vie à l’extérieur du Canada. Il a vécu à Montréal pendant huit ans avant de demander sa naturalisation. L’obtention de la citoyenneté était une entreprise particulièrement difficile pour les immigrants comme Cheeping, compte tenu de la discrimination de l’État et de la société canadienne contre les Chinois, concrétisée par la Loi sur l’immigration chinoise de 1885 qui restreignait l’immigration chinoise au Canada en imposant une taxe d’entrée de 50 $ à chaque personne chinoise cherchant à entrer. Arrivé au Canada deux ans avant la mise en place de la taxe d’entrée, Wong Cheeping n’a pas dû payer de frais. Cependant, sa demande de citoyenneté coïncide avec le déploiement de la taxe, et le sentiment qui la sous-tendait - un désir de garder les Chinois hors du Canada - a probablement influencé le processus de naturalisation de Wong Cheeping. Il prête serment le 2 novembre 1891 (« Naturalized as British Subjects ») et reçoit ses documents officiels de citoyenneté en janvier 1892.

Il y a peu de détails sur les années qui ont précédé l’arrivée de Wong Cheeping à Montréal ou les années passées à Montréal avant sa naturalisation. Sa signature sur l’accord commercial de la Tye Loy Company suggère qu’il a vécu à New York avant ou en même temps que sa résidence à Montréal, mais nous avons peu de sources sur sa présence à New York. Wong Cheeping est peut-être arrivé au Canada après s’être déjà établi aux États-Unis en tant que marchand, un métier qui sera plus tard exonéré de la taxe d’entrée, suggérant que l’État canadien cherchait à attirer ces individus pour leurs potentiel financier. Selon Eaton, Wong Cheeping est devenu assez à l’aise en anglais et s’est familiarisé avec les coutumes sociales du Canada (« Girl Slave ») au cours des huit années précédant sa naturalisation, ce qui aurait été plus faciles à accomplir s’il avait été financièrement en sécurité et n’avait pas à s’inquiéter de la recherche d’un emploi. La stabilité financière lui aurait également permis d’accéder à des cercles sociaux susceptibles de lui enseigner les mœurs et les coutumes canadiennes. De plus, cela lui aurait permis de subvenir aux besoins de sa cousine «brillante et intelligente» (« Girl Slave ») âgée de seize ans qui fréquentait l’école à Montréal.

En 1896, Wong Cheeping retourne en Chine en compagnie de Sin Chow Kee (沈洲紀) et Sin Kee (沈紀), deux autres marchands associés à la Tye Loy Company (« Briefs »). On ne sait pas s’il est revenu ou non à Montréal après ce voyage. Il confie la société Tye Loy à son partenaire commercial Lou Chan Hoy (« Will Bring His Wife Here »), suggérant que son voyage serait un retour prolongé, voire permanent, en Chine pour rejoindre sa femme. Par la suite, les traces de la présence de Wong Cheeping dans les journaux montréalais disparaissent. Il est possible qu’il soit retourné à Montréal, mais cela n’a jamais été rapporté car il n’a pas rejoint Tye Loy. Ou peut-être a-t-il décidé de ne pas revenir, car la taxe pour faire venir sa famille au Canada aurait été trop élevée. Peut-être s’est-il réinstallé à New York. Quelque soit le chemin emprunté par Cheeping après 1896, son départ du Canada après avoir subi le processus long et ardu de naturalisation, couplé à sa vague présence à New York, présente Wong Cheeping comme une figure transnationale qui a parcouru un chemin complexe, et a vécu une histoire dont Montréal n’est qu’une partie infime

Sources 來源

“Advertisers Business Classified Directory,” Lovell’s Montreal Directory, for 1894-95. Montreal, John Lovell & Son, 1894.

“Briefs.” The Montreal Gazette. 17 Mar. 1896: 3.

Cheeping Wong Naturalization Documents. 15 Jan. 1892. Citizenship Registration, Montreal Circuit Court, 1851 to 1945. RG 6 F3, Volume 896, File 402. Library and Archives Canada. http://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=citregmtlcircou&id=2213&lang=eng.

Eaton, Edith (Unsigned). “Chinamen with German Wives.” Montreal Daily Star. 13 Dec. 1895: 5.

Eaton, Edith (Unsigned). “Chinese Religion. Information Given a Lady by Montreal Chinamen.” Montreal Daily Star. 21 Sep. 1895: 5.

Eaton, Edith (Unsigned). “Girl Slave in Montreal. Our Chinese Colony Cleverly Described. Only Two Women from the Flowery Land in Town.” Montreal Daily Witness. 4 May 1894: 10.

Eaton, Edith (Unsigned). “Like a Laundry Ticket.” Montreal Weekly Witness. 18 Apr. 1894: 5.

Eaton, Edith (Unsigned). “The Chinese and Christmas.” Montreal Daily Star. 21 Dec. 1895: 2.

Eaton, Edith (Unsigned). “The Chinese Colony.” Montreal Daily Star. 15 Jun, 1895: 8.

Helly, Denise. Les chinois à Montréal 1877-1951. Institut québécois de recherche sur la culture, 1987.

“Naturalized as British Subjects.” The Montreal Gazette. 3 Nov. 1891: 3.

“Sociétés et Dissolutions.” La Presse. 11 Apr. 1894: 4.

“Will Bring His Wife Here.” Montreal Daily Star. 23 Mar. 1896: 2.