Wing Sing Family, 1860s-?

Contents: English | 漢語 | Français | Sources 來源 | Images 圖片

English

Mr. and Mrs. Wing Sing: Stereotypes and the Lives of Early Chinese Residents of Montreal

Merchant Family - Community Members

by Ethan Xi Hao Eu

Very little is known about the early life of Montreal businessman Wing Sing (1860s-?). He was born in Canton (now Guangzhou), a city in Southern China heavily involved in foreign trade in the mid-18th century. Perhaps to flee a region destabilized by wars or to pursue economic opportunities in the West that the foreign trade had acquainted him with, Wing Sing migrated to Canada, probably before the imposition of the Head Tax in 1885.

His early days in Canada also remain shrouded in mystery because of the paucity of reliable records and the commonness of his name. Archives housed by Library and Archives Canada (LAC) and contemporaneous Canadian newspapers mention more than a dozen Chinese men in Canada named Wing Sing. This number swells even further if we factor in the fact that most officials and journalists who romanized Chinese names tended to transliterate Chinese names inconsistently (Rao xiii). As a result, variations such as “Win Sing,” “Win Shing,” “Wing Xing,” “Wing Hsing” etc. also add to the confusion when we try to disentangle our Wing Sing from others in the archive. There were roughly six Wing Sings who lived in Montreal around the same period. They could be deduced to be different men sharing the same name because four of them were laundry shop owners working in different parts of the city while the remaining one—who was involved in a famous court case that obliged him to swear before a beheaded rooster—only changed his name from Sue Ming into Wing Sing in 1898 (“Chinamen”; “Ethics”; “Woo Joss”; “Advertisement”; “Pole”).

However, attending to these namesakes’ biographical details including their professions, eventual places of settlement, and associates can narrow down the number of men who might be our Wing Sing. By doing so, a focused—albeit narrow—portrait of Wing Sing as a successful merchant who settled in Montreal some time before 1891 emerges (“The Police Committee”). He is mentioned in Edith Eaton’s journalism as the manager of the Quong Hing boarding house on Lagauchetière street, which he co-owned with Montreal businessman Ho Sang (or Sam) Kee as early as 1894 (Eaton, “Girl Slave”).

In addition to the boarding house on rue de la Gauchetière street, Wing Sing also owned a laundry on Dorchester street (now boulevard Réné Lévesque) and a shop behind St. Lawrence Market (“Novel Case”). Despite his clear success, Wing Sing remained vulnerable to the stereotypes of criminality that dogged early Chinese migrants. In July 1891, he was arrested, along with his wife, because Sergeant Bouchard suspected him of evading the Head Tax when he brought his wife to Canada (“The Police Committee”). However, Wing Sing was released when he produced a certificate indicating that he had paid the tax at Vancouver (“The Police Committee”). To protect his reputation, he engaged the legal services of Messrs. Lighthall & Lighthall and sued the sergeant for his “false arrest” (“The Police”). Furthermore, in 1894, together with Montreal businessman Ho Sang Kee, he was also suspected of contributing to the clandestine operation that smuggled Chinese men over the US border (“Collapse”). While these suspicions were ultimately proved unsubstantiated (“Scharf’s Failure”), their lingering presence prompted prolonged media attention and scrutiny from officials who were “smiling in their sleeves at the denials” coming from these business partners (“The Smuggling”).

Despite lingering suspicion and hostility, Wing Sing and his wife actively participated in community works and were acknowledged to be “leaders of local Chinese society” in Montreal (“Novel Case”). For example, in 1895, Wing Sing participated in an evening performance at the Emmanuel Church organized by Chinese Sunday school students and translated Rev. Mr. Silcox’s address into Chinese (“A Chinese Entertainment”).

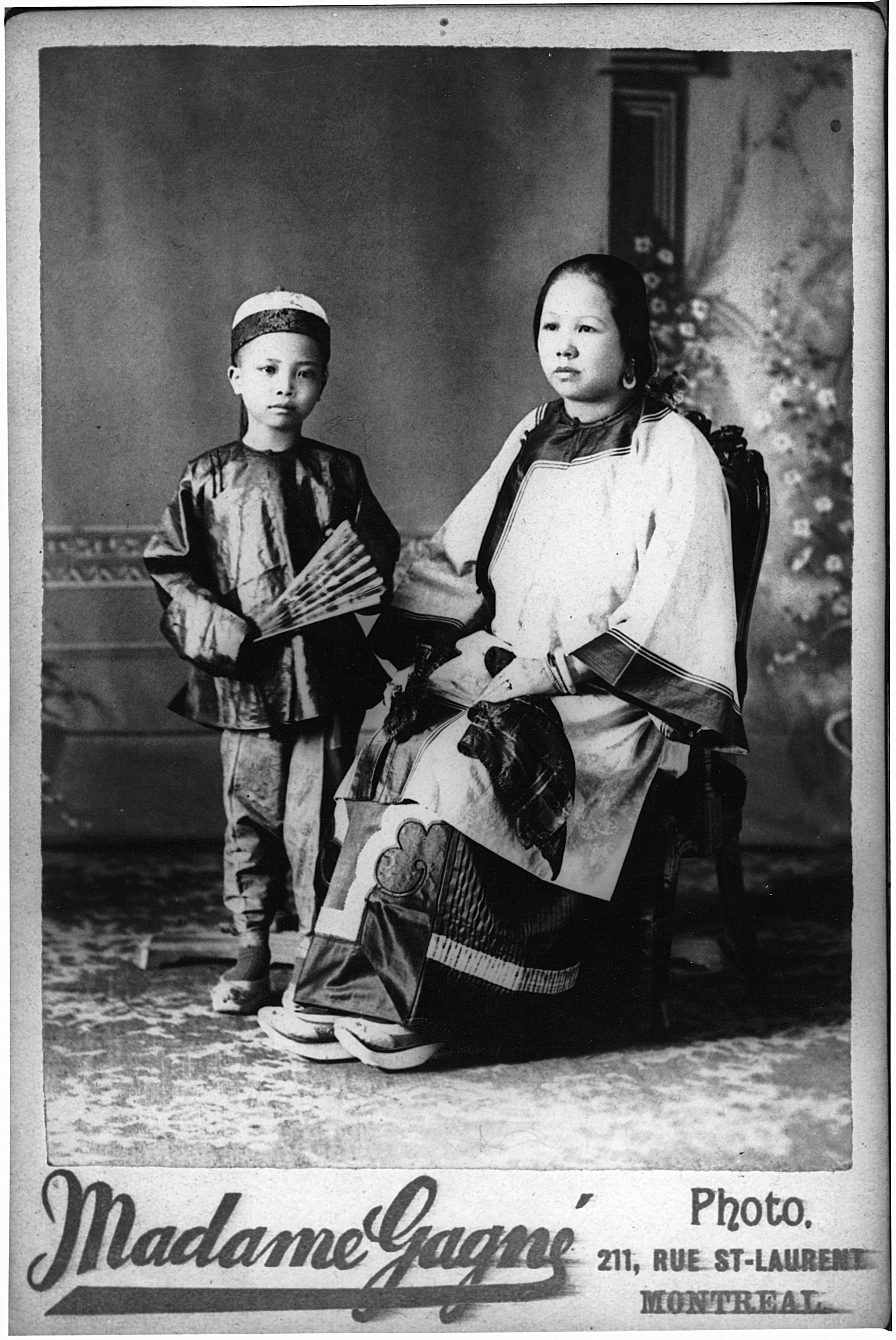

Mrs. Wing Sing, as one of the only three Chinese women in Montreal in 1894 (Eaton, “Girl Slave”), also attracted considerable press attention. Reporters, informed by public fascination and stereotypes, focused on details such as whether her feet were bound. However, they also paid attention to her clothes and jewelry and the furnishings of her apartment. These details—as shown in the portrait and illustration below—give us a glimpse into the Sings’ private lives.

From the fact that she does not wear the Liangbatou (Big Wing headdress), we can deduce that Mrs. Wing Sing was Han, not Manchu (Hsu 11)—a fact that excluded her from the noble class and may explain her willingness to emigrate to Canada. However, her elaborately embroidered underskirt, feathered fan, and jade earrings, as well as her gilded porcelains, embroidered tablecloth, and tapestry attested to the affluence of the Sing household, since most of these would have had to be made by skilled artisans in Qing China and then imported into Canada.

Despite their good fortune, Wing Sing and his wife struggled for many years to have a child (“Color”). In 1903, with the help of Mrs. Joe Pong, they adopted a baby of Irish ancestry (“Color”). They named him You Kang and both doted on him (“Novel Case”). Contemporary news reports noted that Mr. Wing Sing often carried You Kang around in front of his shop near St. Lawrence Market so that they could enjoy the sunshine together (“Novel Case”). Writing a travelogue from the perspective of a fictional “Wing Sing” discussing his cousin’s adoption of a white baby, Edith Eaton similarly reported that Wing Sing and his wife often forgot “the rules of propriety” and gave baths to the baby together (Eaton, “Wing Sing”).

漢語

Wing Sing 夫婦:蒙特利爾早期華人的刻板印象與生活

商人家庭 - 社區成員

作者 Ethan Xi Hao Eu

我們對蒙特利爾商人文興(音譯自Wing Sing)的早年生活知之甚少。他出生於廣州,中國南方的一座在 18 世紀中葉大量參與對外貿易的城市 。 也許是為了逃離這個因戰爭而動盪不安的地區,也或者是為了在西方尋求他接觸外貿時熟悉的經濟機會,文興在大約 1885 年徵收人頭稅之前移居加拿大。

他在加拿大的早期生活也一直籠罩在神秘之中。這主要歸咎為文興(Wing Sing)這個名字的普遍性和可靠的檔案的缺乏。加拿大圖書館和檔案館 (Library and Archives Canada) 收藏的檔案裡和同時期的加拿大報紙中提到了十幾名在加拿大居留, 名為文興(Wing Sing)的華人。這個數字會進一步膨脹,如果我們考慮到當時大多數負責將中文名字羅馬化的官員和記者不會說中文, 並且傾向於非系統性地音譯中文名字這些事實。因此,當我們試圖將我們的文興(Wing Sing) 與檔案中的其他人分開時,諸如“Win Sing”、“Win Shing”、“Wing Xing”、“Wing Hing”等變體也會增加混亂。

然而,我們可以通過關注這些同名人士的履歷細節(包括他們的職業,最終定居地和同事)來縮小可能成為蒙特利爾商人文興的人數。通過這樣做,我們可以為蒙特利爾商人文興寫一個細緻但狹小的描述。文興是一位成功的商人, 他在 1891 年之前的某個時間點裡移居到蒙特利爾(“The Police Committee”)。伊迪絲·伊頓 (Edith Eaton) 的新聞報導中提到說他早在 1894 年時,就與另一個蒙特利爾商人 Sam(或 Sang)Kee 一同共同經營位於 Lagauchetière 街的 Quong Hing 寄宿處(Eaton, “Girl Slave”)。

除了位於 Lagauchetière 街的寄宿處外,文興也經營 Dorchester 街(現為 Réné Lévesque 大道)上的一家洗衣房,和 St. Lawrence Market(“Novel Case”)後方的一家商店。儘管他取得了顯著的成功,文興仍然受到早期加拿大對中國移民的犯罪刻板印象的影響和困擾。 在1891 年 7 月,他與妻子一起被捕,原因是布沙爾中士(Sergeant Bouchard)懷疑他在將妻子帶到加拿大時逃避了人頭稅(“The Police Committee”)。然而,文興出示證明顯示說他已在溫哥華繳了人頭稅,並因此獲得了保釋(“The Police Committee”)。為了維護自己的名譽,他聘請了律師事務所Messrs. Lighthall & Lighthall的法律服務,並控告該中士“非法拘留”他和他太太(“The Police”)。此外,在 1894 年,他也和 Sang Kee 一起被懷疑參與了一系列將中國移民非法偷渡過美國邊境的秘密行動(“Collapse”)。雖然這些懷疑最終被證明是沒有根據的(“Scharf’s Failure”),這些懷疑依然揮之不去, 也引起了媒體的長期關注和官員的審查。這些人士表示來自於這兩位商業夥伴的否認很“荒唐可笑”(“The Smuggling”)。

儘管懷疑和敵意揮之不去,文興夫婦還是積極參與社區工作,也因此被公認為蒙特利爾“當地華人社會的領袖”(“Novel Case”)。例如說在1895年,文興參加了華人主日學學生組織的晚間演出,也在大會中將席爾考克斯牧師 (Rev. Mr. Silcox)在靈光堂(Emmanuel Church)的致辭翻譯成中文(“A Chinese Entertainment”)。

文興夫人,作為1894年在蒙特利爾僅有的三位華人女性之一(Eaton, “Girl Slave”),也引起了媒體的廣泛關注。記者們因受到了公眾的興趣和刻板印像的影響,重點關注了她是否有纏小腳和纏足等細節。不過,他們也詳細描述了她的衣服、首飾和她公寓的擺設。這些細節—如下面的肖像和插圖所示—讓我們得以一窺文興夫婦的私生活。 從她沒有戴旗頭(Liangbatou)這一點,我們可以推斷出文興夫人是漢人,而不是滿人(Hsu 11)。這一事實將她排除在貴族階層之外,並可能解釋了她願意移民到加拿大的原因。 然而,她精心繡製的襯裙、羽扇和玉耳環,以及她的鍍金瓷器、繡花桌布和掛毯證明了文興家的富裕。這些精緻用品必須由中國清代的巧匠製作,然後進口到加拿大。

儘管家境殷實,文興和他的妻子多年來一直求子不果(“Color”)。 在1903年,他們在Joe Pong夫人的幫助下收養了一名有愛爾蘭血統的嬰兒(“Color”)。他們把他命名為永康(音譯自You Kang),並對他悉心寵愛(“Novel Case”)。當代新聞報導稱說,文興先生經常背著永康在他位於聖勞倫斯市場附近的商店門前四處走動,一起享受陽光(“Novel Case”)。伊迪絲·伊頓(Edith Eaton)曾用筆名文興(Wing Sing)寫了一系列遊記,並在遊記裡討論說他的堂兄收養了一個白人嬰兒。在這些遊記裡,她同樣報導說文興和他的妻子經常不顧“禮儀”,一起給嬰兒洗澡(Eaton, “Wing Sing”)。

Français

M et Mme Wing Sing: Les stéréotypes et la vie des premiers résidents chinois de Montréal

Famille de Marchands - Membres de la Communauté

Par Ethan Xi Hao Eu

On sait très peu de choses sur les débuts de l’homme d’affaires montréalais Wing Sing. Il est né à Canton (aujourd’hui Guangzhou), une ville du sud de la Chine fortement impliquée dans le commerce extérieur au milieu du XVIIIe siècle. Wing Sing a émigré au Canada, probablement avant l’imposition de la taxe d’entrée en 1885, peut-être pour fuir une région déstabilisée par les guerres ou pour poursuivre des opportunités économiques dans l’Ouest que le commerce extérieur lui avait fait connaître.

Les débuts de la vie de Wing Sing au Canada restent également mystérieux en raison de la rareté des documents fiables et de la banalité de son nom. Les archives de la Bibliothèque et Archives du Canada et les journaux canadiens contemporains mentionnent plus d’une douzaine d’hommes chinois au Canada nommés Wing Sing. Ce nombre augmente encore plus si l’on tient compte du fait que la plupart des fonctionnaires et des journalistes qui romanisaient les noms chinois ne parlaient pas chinois et avaient tendance à translittérer les noms chinois de manière incohérente. Par conséquent, des variations telles que « Win Sing », « Win Shing », « Wing Xing », « Wing Hsing », etc. ajoutent également à la confusion lorsque nous essayons de distinguer notre Wing Sing des autres dans l’archive. Il y a eu environ six Wing Sing qui ont vécu à Montréal à la même époque. On peut en déduire qu’il s’agit d’hommes différents partageant le même nom, car quatre d’entre eux étaient des propriétaires de blanchisseries travaillant dans différents quartiers de la ville, tandis que le dernier - qui a été impliqué dans une célèbre affaire judiciaire qui l’a obligé à jurer devant un coq décapité - n’a changé son nom de Sue Ming en Wing Sing qu’en 1898 (« Chinamen »; « Ethics »; « Woo Joss »; « Advertisement »; « Pole »).

Cependant, l’examen des détails biographiques de ces homonymes, y compris celui de leurs professions, de leurs éventuels lieux d’établissement et de leurs associés peut réduire le nombre d’hommes qui pourraient être le Wing Sing de Montréal. Ce faisant, un portrait ciblé, bien qu’ étroit, du Wing Sing qui s’est installé à Montréal quelque temps avant 1891 en tant que marchand prospère émerge (« Le Comité de police »). Il est mentionné dans les articles d’Edith Eaton comme gérant de la pension Quong Hing rue de la Gauchetière dont il est copropriétaire avec l’homme d’affaires montréalais Ho Sang (ou Sam) Kee dès 1894 (Eaton, « Girl Slave »).

En plus de la pension rue de la Gauchetière, Wing Sing possède également une blanchisserie rue Dorchester (aujourd’hui boulevard Réné Lévesque) et un magasin derrière le marché Saint-Laurent (« Novel Case »). Malgré son franc succès, Wing Sing est resté sujet aux stéréotypes de criminalité qui pèsent sur les premiers migrants chinois. En juillet 1891, il est arrêté, ainsi que sa femme, parce que le sergent Bouchard le soupçonne d’avoir éludé la taxe d’entrée en amenant sa femme au Canada (« The Police Committee »). Toutefois, Wing Sing a été libéré lorsqu’il présente un certificat indiquant qu’il avait payé la taxe à Vancouver (« The Police Committee »). Pour protéger sa réputation, il fait appel aux services juridiques de Messieurs Lighthall & Lighthall et poursuit le sergent pour son «arrestation arbitraire » (« The Police »). De plus, en 1894, avec Sang Kee, il est également soupçonné d’avoir contribué à l’opération clandestine de passage d’hommes chinois à la frontière américaine (« Collapse »). Bien que ces soupçons se soient finalement avérés infondés (« Scharf’s Failure »), leur présence persistante a suscité une attention spéciale de la part des médias et un examen minutieux de la part des fonctionnaires qui « souriaient sous couvert à ces dénégations » venant de ces partenaires commerciaux (« The Smuggling »).

Malgré la méfiance et l’hostilité persistantes, Wing Sing et sa femme participent activement aux travaux communautaires et sont reconnus comme des « leaders de la société chinoise locale » à Montréal (« Novel Case »). Par exemple, en 1895, Wing Sing participe à une soirée à L’église Emmanuel organisée par des étudiants chinois de l’école du dimanche et traduit en chinois le discours du révérend M. Silcox (« Un divertissement chinois » ).

Mme Wing Sing, l’une des trois seules femmes chinoises à Montréal en 1894 (Eaton, « Girl Slave »), attire également l’attention de la presse. Les journalistes, influencés par la fascination du public et les stéréotypes, se concentrent sur des détails comme le fait de savoir si elle avait les pieds liés. Cependant, ils ont également prêté attention à ses vêtements et à ses bijoux ainsi qu’à à l’ameublement de son appartement. Ces détails, comme le montrent le portrait et l’illustration ci-dessous, nous donnent un aperçu de la vie privée des Sing.

Du fait qu’elle ne porte pas le Liangbatou (coiffe à grandes ailes), nous pouvons déduire que Mme Wing Sing était Han, et non pas Manchu (Hsu 11) - ce qui l’ exclut de la classe noble et peut expliquer sa volonté d’émigrer au Canada. Cependant, son jupon richement brodé, son éventail à plumes et ses boucles d’oreilles en jade, ainsi que ses porcelaines dorées, sa nappe brodée et sa tapisserie attestent de la richesse de la maison Sing, car la plupart d’entre eux auraient dû être fabriqués par artisans qualifiés de la Chine Qing, puis importés au Canada.

Malgré leur bonne fortune, Wing Sing et sa femme ont lutté de nombreuses années pour avoir un enfant (« Color » ). En 1903, avec l’aide de Mme Joe Pong, ils adoptent un bébé d’origine irlandaise ( « Color » ); ils l’appellent You Kang et le chérissent (« Novel Case »). Des reportages contemporains ont noté que M. Wing Sing portait souvent You Kang devant son magasin autour du marché St. Lawrence afin qu’ils puissent profiter du soleil ensemble (« Novel Case »). Dans un carnet de voyage écrit du point de vue d’un Wing sing fictif, Edith Eaton raconte que Wing Sing et sa femme oubliaient souvent «les règles de bienséance» et donnaient des bains au bébé ensemble. (Eaton, « Wing Sing » ).

Sources 來源

“A Chinese Entertainment.” The Montreal Gazette. 27 Mar 1895: 3.

Advertisement for Wing Sing Laundry. The Montreal Star. 10 Sep 1904: 13.

Chapman, Mary, ed. Becoming Sui Sin Far. McGill-Queen’s UP, 2016.

“Chinamen Fined.” The Montreal Gazette. 23 Oct 1900: 3.

“Collapse of a Sensation.” The Montreal Daily Star. 14 Jul 1894: 4.

“Color No Obstacle.” The Montreal Gazette. 24 Sep 1903: 3.

[Eaton, Edith]. “Girl Slave in Montreal.” Montreal Daily Witness, 4 May 1893: 10.

[Eaton, Edith]. “The Chinese Colony.” The Montreal Daily Star. 15 Jun 1895: 8.

[Eaton, Edith]. “Wing Sing in Montreal.” Los Angeles Express. 12 Mar 1904: 6.

Elliott, Mark C. The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China. Stanford UP, 2001.

“Ethics of Wing Sing.” The Montreal Gazette. 30 Aug 1898: 3.

Hsu, Tung [徐冬]. Chi-Pao [旗袍]. Mercury Book Publishing [水星文化事業出版社], 2013.

Mrs. Wing Sing, Montreal, QC, about 1895. McCord Stewart Museum, https://collections.musee-mccord-stewart.ca/en/objects/156240/mrs-wing-sing-montreal-qc-about-1895.

“Novel Case of Child Adoption.” The Montreal Daily Star. 23 Sep 1903: 6.

o, Chung-yam. Conceptualizing the Blue Frontier: The Great Qing and the Maritime World in the Long Eighteenth Century. 2013. Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg, PhD Dissertation.

“Pole Disliked Chinamen and Kicked in Thirty-Dollar Laundry Window.” The Montreal Gazette. 26 Sep 1913: 3.

Rao, Nancy Yunhwa. “A Note on Chinese Names and Terms.” Chinatown Opera Theater in North America, U of Illinois P, 2017, pp. xiii-xiv.

“Scharf’s Failure to Prove.” The Montreal Star. 3 Aug 1894: 6.

“The Police Committee.” The Montreal Gazette. 6 Aug 1892: 7.

“The Police Committee.” The Montreal Gazette. 7 Oct 1892: 2.

“The Smuggling of Chinese.” The Montreal Daily Star. 26 April 1895: 3.

“Woo Joss in Court.” The Montreal Gazette. 1 Sep 1898: 3.