Ho Sang Kee (1859-1949)

Contents: English | 漢語 | Français | Sources 來源 | Images 圖片

English

Ho Sang Kee: At the Heart of Montreal’s Early Chinese Community

Hotelier – Advocate – Father

by Delaney Anderson

Ho Sang Kee (also known as “Sang Kee,” “Haw Sang Kee,” “Sam Kee,” “San Kee,” and “Charlie Hore Sang”) was born in 1859 in Guangdong Province, China. Around 1878, he made the journey across the Pacific and began making and saving money in Canada. Initially, Ho Sang Kee lived in Toronto and attended a Chinese Sunday School in the city. He would also begin his employment with the Canadian Pacific Railway sometime after its incorporation in 1881, as he would later take a contract from the company to board Chinese passengers travelling across the country, and it is possible that was the same “Sang Kee” who served as the CPR’s first Chinese interpreter. However, it was in 1890s Montreal where Ho Sang Kee would become a pivotal early Chinese figure in Canada as a successful businessman, naturalised British citizen, and point-of-contact for thousands of Chinese men travelling across the continent during a period of anti-Chinese legislation in both Canada and the United States.

Upon moving to Montreal, Sang Kee established the Quong Hing Tea Co. wholesale retailer, grocery, and boarding house on rue de la Gauchetière in the heart of Montreal’s Chinatown, and he quickly became one of the central figures in Montreal’s Chinese community. At its inception in 1891, Quong Hing Tea Co. was the only non-laundry Chinese-owned business in the city. The ground floor of the building at 625, rue de la Gauchetière consisted of a cooking and lounging room along with a shop stocked with Chinese goods, while the upper three stories comprised his own residence and sleeping quarters that consistently housed 30 to 40 Chinese men but sometimes hosted as many as 70 guests at once. The company name soon became synonymous with his own; some newspapers even referred to Ho Sang Kee as “Sam Quong” or, simply, “Quong Hing”. This could not have been an easy business for Ho Sang Kee, and his career was certainly not without its share of troubles. Police raided his building multiple times during the 1890s, resulting in arrests of his patrons and himself on suspicion of opium smuggling and gambling, but he continued to operate his establishment despite pushback from law enforcement, even suing the City of Montreal for “false arrest” in the latter case.

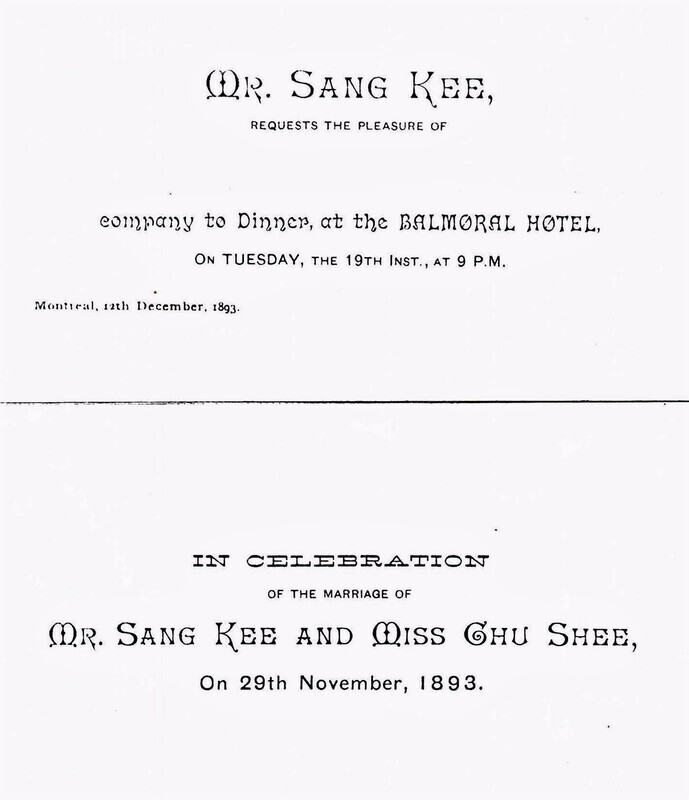

In October 1892, while staying at Ottawa’s Russell House Hotel, Ho Sang Kee made “enquiries touching the scope of the Dominion laws as applied to his countrymen”; in other words, he went directly to the Canadian capital with his concerns about the federal Head Tax legislation excluding Chinese people from entering Canada unless they paid hefty fees. It was likely around this time that he was sworn in as a naturalised British citizen by Judge Louis Wilfrid Sicotte in Montreal, though official records of this have not been found. Ho Sang Kee’s future wife Chu Shee would arrive in Vancouver from China on November 21, 1893, and by November 29, the two had married in Montreal’s first Chinese wedding. Ho Sang Kee hosted an enormous banquet at Montreal’s Balmoral Hotel on December 19. Guests included members of the local Chinese community, American politicians, deputy collectors, officials from the CPR, and local journalists. Even Judge Sicotte received one of Ho Sang Kee’s “exceedingly neat and pretty” invitations printed on lavender card.

Six months later, on June 23, 1894, The Montreal Star reported that “the floating population of Chinese in Montreal has been diminished” by an “exodus” of at least 150 men to the United States, and a few weeks later, Sang Kee was arrested in Boston for his alleged involvement in smuggling Chinese men over the U.S. border via an “underground route”. He was released on bail and was back at 625, rue de la Gauchetière by August 6, where he was met by reporters from The Boston Globe and agreed to give an interview. When asked about the smuggling allegations, he made an “emphatic and indignant denial”. The interviewer inquired whether or not he was afraid to return to the United States, to which he replied: “Why not? My business is there and in Montreal. I not afraid they will arrest me. [U.S. Chinese Inspector Thomas J.] Scharf is the man; he will be arrested”, all while “laugh[ing] merrily at his own humor”. Three days earlier, news reached Montreal that Inspector Scharf had been met with a $10,000 lawsuit in New York after being unable to provide evidence to prove his story about the nature of the alleged smuggling operation. The Montreal Star reported that Sang Kee was “delighted with the news” about the lawsuit facing Scharf.

Ho Sang Kee’s and his wife’s son George (Georgie) was born at the boarding house the following year, on September 29, 1895, and author Edith Eaton (Sui Sin Far) described Sang Kee as “wreathed with smiles” while celebrating his son’s birth. In January 1898, Quong Hing Tea Co. was still receiving many Chinese visitors but by the time Lovell’s Directory for 1898-1899 was published, 625, rue de la Gauchetière would be listed as vacant. Ten years later, in 1908, Ho Sang Kee’s wife and twelve-year-old son George died months apart and were buried at Montreal’s Mount Royal cemetery. Tuberculosis was ravaging Montreal in 1908 at a disproportionate rate compared to other Canadian cities, resulting in upwards of 1000 deaths per year by that time, and Sang Kee’s family may have been victims of this devastating “white plague”. After this period, Ho Sang Kee’s name disappears from the press and from the public record altogether. He was, apparently, working in the west at this time, and his children were fostered by the Wilson family in Quebec City. By the 1930s, Ho Sang Kee was living with his daughter Avis, who was married to James Lee. Ho Sang Kee died in 1949 and is buried at Cimetière Urgel Bourgie in Montreal.

Ho Sang Kee became more wary of newspapermen as the 1890s progressed, likely due in no small part to the sensational headlines and stories printed about him across the continent. One British Columbian newspaper referred to him as both “the Eastern Smuggling King” and the “Prince of Smugglers” in the same short article, and much of the press about him across North America was equally unsavoury. Perhaps this media frenzy surrounding his existence prompted a retreat from the public eye. However, he figures quite prominently and favourably in Edith Eaton’s Montreal journalism from the 1890s, and he evidently had a wide circle of family, friends, associates, and connections in both Canada and the United States. The Boston Globe reported on a Boston wedding banquet in celebration of Mr. and Mrs. Sang Kee held only days before their banquet in Montreal, and noted that “all the elite of Chinatown” and “many prominent Americans including government officials in Burlington and Boston” were invited. Eaton describes a flood of congratulatory messages for Ho Sang Kee pouring into Montreal “from friends in Boston and New York” when his son George was born in 1895. Despite the present mysteries that remain unsolved about his life, it is clear that Ho Sang Kee lived at the heart of a transnational community of Chinese North Americans, and facilitated the sheltering of thousands of Chinese men in his Montreal boarding house during a tumultuous time when Canada and the United States endeavoured to legislate them out of sight.

漢語

Ho Sang Kee: 位於蒙特利爾早期華人社區的中心

酒店經營者 - 倡導者 - 父親

作者 Delaney Anderson

何生記(又名“生記”、“Haw Sang Kee”、“Sam Kee”、“San Kee”及“查理·Hore Sang)出生於1859年的中國廣東省。 1878年前後,他橫渡太平洋,開始在加拿大賺錢和存錢。起初,他住在多倫多,就讀於市的華人主日學校。他或許是在 1881 年之後開始在加拿大太平洋鐵路公司工作,因為他後來與該公司簽約,為穿越加國的華人乘客提供登車服務。他有可能和加拿大太平洋鐵路公司的第一位中文翻譯“生記”是同一人。然而,何生記成為加拿大早期華人的關鍵人物,要等到1890 年代的蒙特利爾。他成為了一名成功的商人、歸化入籍的英國公民,也充當了美加兩國排華時代,數千名華人穿越大陸旅行時的的聯絡人。

移居蒙特利爾後,生記在蒙特利爾唐人街中心的德拉高謝蒂埃街(Rue de La Gauchetière)街成立了Quong Hing茶葉有限公司(Quong Hing Tea Co.)批發零售商、雜貨店和寄宿處。他並迅速成為蒙特利爾華人社區的核心人物之一。 在1891 年成立時,廣興茶業是該市唯一一家非洗衣店的華人企業。德拉高謝蒂埃街625 號大樓的首層包括一間廚房兼休息室以及一間备有中國商品的商店,而上面的三層樓由他自己的住所和許多寄宿單元組成。這些空間一直都可以容納30至40名中國男性,但有時一次接待多達70位客人。公司名稱很快成為何生記自己的代名詞;一些報章甚至稱生記為“Sam Quong”,或簡稱為“Quong Hing”。從事這行業對何生記來說並不容易; 他的職業生涯當然也不是一帆風順。整個 1890 年代,警方多次突擊搜查他的建築物。這導致他的顧客,以及他本人,因涉嫌鴉片走私和賭博而被捕。但儘管遭到執法部門的阻撓,他仍繼續經營該機構,甚至在他自己遭到逮捕後,以“錯誤逮捕”的罪名起訴了蒙特利爾市政府。

1892 年 10 月,在渥太華的 Russell House 旅館住宿期間,何生記對“自治領法律範圍內,適用於他的同胞的條款發起質詢”;換句話說,他直接前往加拿大首都,表達了他對聯邦人頭稅法規定中國人必須支付高額費用才准許入境的擔憂。或許在這個時候,他在蒙特利爾由法官路易斯·威爾佛里德·西科特(Louis Wilfrid Sicotte)宣誓歸化成為英國公民,但有關此事件的法庭記錄尚未找到。 1893 年 11 月 21 日,何生記未來的妻子朱西(Chu Shee)從中國抵達溫哥華。 11 月 29 日,兩人在蒙特利爾舉行了第一場華人婚禮。這對夫婦於 12 月 19 日在蒙特利爾的巴爾莫勒爾酒店舉辦了一場盛大的宴會。賓客包括當地華人社區成員、美國政界人士、副稅收員、加拿大太平洋鐵路官員和當地記者,甚至西科特法官也收到了何生記的一張“極度整潔漂亮”的邀請卡。

六個月後,即 1894年6月23日,《蒙特利爾星報》報導稱,“蒙特利爾的華人流動人口已經減少”,至少有150 名男子“外流”到美國。幾週後,何生記因涉嫌參與通過“地下路線”將中國男子偷運到美國邊境而在波士頓被捕。他獲得保釋,並於 8 月 6 日回到德拉高謝蒂埃街625 號。在那裡他與《波士頓環球報》的記者會面並同意接受采訪。當被問及關於走私的指控時,他“堅決且憤憤不平地進行了否認”。採訪者進一步詢問他是否害怕回到美國。他回答說:“有什麼理由不回?我的生意在美國及蒙特利爾兩邊都有。我不怕他們會逮捕我。[負責華人事務的美國警督托馬斯 J.] 沙爾夫 (Thomas J. Sharf) 才是那個需要被逮捕的人”,他說這番話時“對自己的幽默忍俊不禁”。在那之前三天,新聞已經傳到蒙特利爾,警督沙爾夫因無法提供證據佐證他關於何生計走私行為的指控,在紐約面臨一萬美元的訴訟。《蒙特利爾之星》報導說,何生記對沙爾夫面臨的訴訟“感到高興”。

次年,即1895年9月29日,何生記的兒子喬治(George / Georgie)在寄宿房出生。作家伊迪絲·伊頓(Edith Eaton, Sui Sin Far,中文名也写作水仙花)形容何生記在慶祝兒子出生時“沉浸在喜悦当中”。直到1898 年 1 月,Quong Hing茶業有限公司仍接待許多华人来客。然而,當 Lovell 目錄 1898-1899 年出版時, 德拉高謝蒂埃街625 號被列為空置。十年後, 1908 年,生記夫人和十二歲的喬治于數月内相繼去世,葬於蒙特利爾的皇家山公墓。1908 年,與加拿大其他城市相比,蒙特利爾以不成比例的速度被結核病蹂躪。那時候,結核病每年導致超過 一千人死亡。何生記的家人或許是這場毀滅性“白色瘟疫”的受害者。此後不久,何生記的名字就完全從媒體和公共記錄上消失了。他當時顯然在西部工作,而他的孩子被居住在由魁北克市的威爾遜(Wilson)家族撫養。到了1930年,何生記與他的女兒 Alvis 住在一起;Alvis 嫁給了 James Lee。何生記於1949年去世。他被埋葬在蒙特利爾,Urgel Bourgie公墓。

随着1890 年代的進程,何生記對新聞記者變得更加警惕。一個重要原因或許是新闻媒体在整个大陆范围内刊登的關於他的聳人聽聞的頭條新聞和故事。不列顛哥倫比亞省的一家報紙在同一篇短文中稱他為“東方走私大王”和“走私王子”。北美的許多媒體對他同樣表示反感。也許這種圍繞他的存在的媒體狂熱促使他從公眾視線中撤退。然而,他在伊迪絲·伊頓 (Edith Eaton) 与1890年代做的的蒙特利爾新聞报道中佔據了相當突出和受歡迎的地位,而且他顯然在加拿大和美國都有廣泛的家人、朋友、同事和關係。《波士頓環球報》報導, 在蒙特利爾宴會之前幾天,為慶祝何生記夫婦婚礼而举行的波士頓婚宴中,受邀出席的有“所有唐人街的精英”以及“包括伯靈頓和波士頓政府官員在內的許多美國知名人士”。伊頓描述說,當何生記的兒子喬治於 1895 年出生時,“波士頓和紐約的朋友”向蒙特利爾寄來了洪水般的祝福信息。儘管目前關於他的人生仍存有未解開的謎團,但很明確的是,何生記生活在北美華人跨國社區的中心。此外,他在加拿大與美國試圖通過立法將華人們排除在人們的視線之外的動盪時期,幫助了数千名中國男人在他的蒙特利爾寄宿處避難。

Français

Ho Sang Kee : Au cœur de la première communauté chinoise de Montréal

Hôtelier - Défenseur - Père

Ho Sang Kee (également connu sous le nom de « Ho Sang Kee », « Sam Kee » et « San Kee ») est né en 1859 dans la province du Guangdong, en Chine. Vers 1878, il traverse le Pacifique et commence à gagner et à économiser de l’argent au Canada. Dans un premier temps, Sang Kee vit à Toronto et fréquente l’école du dimanche chinoise de la ville. Il commence également à travailler pour le Chemin de fer Canadien Pacifique (CFCP) peu après son incorporation en 1881, puisqu’il accepte plus tard un contrat de la compagnie pour embarquer des passagers chinois voyageant à travers le pays. Il est possible qu’il soit le même « Sang Kee » qui a servi de premier interprète chinois du CFCP. Cependant, c’est dans les années 1890 à Montréal que Sang Kee deviendra une des premières figures centrales chinoises au Canada, en tant qu’homme d’affaires prospère, citoyen britannique naturalisé et point de contact pour des milliers d’hommes chinois voyageant à travers le continent, à une époque où la législation anti-chinoise est en vigueur au Canada et aux États-Unis.

En s’installant à Montréal, Sang Kee fonde la Quong Hing Tea Co., un commerce de gros, une épicerie, et une pension de famille dans la rue de la Gauchetière, au cœur du quartier chinois de Montréal, et devient rapidement l’une des figures de proue de la communauté chinoise de Montréal. Au moment de sa création en 1891, la Quong Hing Tea Co. était la seule entreprise chinoise de la ville à ne pas être une blanchisserie. Le rez-de-chaussée de l’immeuble du 625 rue de la Gauchetière se composait d’une salle de cuisine et de séjour ainsi que d’un magasin rempli de produits chinois, tandis que les trois étages supérieurs comprenaient sa propre résidence et les nombreuses chambres à coucher qui abritaient 30 à 40 hommes chinois mais qui parfois accueillait jusqu’à 70 invités à la fois.

Le nom de l’entreprise devient rapidement synonyme du sien; certains journaux appellent même Ho Sang Kee « Sam Quong » ou, plus simplement, « Quong Hing ». Cependant, la carrière de Sang Kee est parsemée d’embûches et il rencontre son lot de problèmes. La police fait plusieurs descentes dans son immeuble au cours des années 1890, ce qui entraîne son l’arrestation ainsi que celle de ses clients, soupçonnés de contrebande d’opium et de jeu, mais il continue de faire tourner son établissement malgré la répression des forces de l’ordre, allant même jusqu’à poursuivre la ville de Montréal pour « arrestation injustifiée » dans ce dernier cas.

En octobre 1892, alors qu’il séjourne à l’hôtel Russell House d’Ottawa, Sang Kee se renseigne sur la portée des lois du Dominion qui s’appliquent à ses compatriotes ; en d’autres termes, il se rend directement dans la capitale canadienne avec ses inquiétudes au sujet de la législation fédérale sur la taxe d’entrée qui empêche les Chinois d’entrer au Canada sans payer de lourds frais. C’est probablement à cette époque qu’il a été assermenté en tant que citoyen britannique naturalisé par le juge Louis Wilfrid Sicotte à Montréal, bien qu’aucun document officiel n’ait été trouvé à ce sujet. La future épouse de Sang Kee, Chu See arrive à Vancouver en provenance de Chine le 21 novembre 1893 et, le 29 novembre, les deux se marient lors de ce qui devient le premier mariage chinois à Montréal. Ho Sang Kee organise un énorme banquet à l’hôtel Balmoral de Montréal le 19 décembre. Parmi les invités figurent des membres de la communauté chinoise locale, des politiciens américains, des collectionneurs adjoints, des représentants du CFCP et des journalistes locaux. Même le juge Sicotte reçoit l’une des cartes d’invitation « extrêmement soignées et jolies » de Sang Kee, imprimées sur des cartes de couleur lavande..

Six mois plus tard, le 23 juin 1894, le Montreal Star rapporte que « la population flottante de Chinois à Montréal a été diminuée » par un « exode » d’au moins 150 hommes vers les États-Unis, et quelques semaines plus tard, Ho Sang Kee est arrêté à Boston pour son implication présumée dans le passage clandestin d’hommes chinois à la frontière américaine via une « route souterraine ». Libéré sous caution, il est de retour au 625, rue de la Gauchetière, le 6 août, où il est accueilli par des journalistes du Boston Globe et accepte de donner une interview. Interrogé sur les allégations de contrebande, il nie de manière « catégorique et indignée ». L’intervieweur lui demande ensuite s’il a peur de retourner aux États-Unis, ce à quoi il répond : « Pourquoi pas ? Mon entreprise est là-bas et à Montréal. Je n’ai pas peur qu’ils m’arrêtent. [L’inspecteur chinois américain Thomas J.] Scharf est le coupable ; il sera arrêté », tout en « riant avec enthousiasme de son propre humour ». Trois jours plus tôt, la nouvelle était parvenue à Montréal que l’inspecteur Scharf avait fait l’objet d’une poursuite de $10 000 à New York après avoir été incapable de fournir des preuves sur la nature de l’opération de contrebande présumée. Le Montreal Star rapporte alors que Ho Sang Kee était « ravi de la nouvelle » concernant la poursuite intentée contre Scharf.

George (Georgie), le fils de Ho Sang Kee et de sa femme, naît à la pension l’année suivante, le 29 septembre 1895, et l’auteur Edith Eaton (Sui Sin Far) décrit Ho Sang Kee comme «entouré de sourires” en célébrant la naissance de son fils. En janvier 1898, la Quong Hing Tea Co. recevait encore de nombreux visiteurs chinois, mais au moment de la publication du Lovell’s Directory for 1898-1899, le 625 rue de la Gauchetière est considéré comme vacant. Dix ans plus tard, en 1908, la femme de Ho Sang Kee et son fils George, âgé de douze ans, meurent à quelques mois d’intervalle et sont inhumés au cimetière Mont-Royal de Montréal. En 1908, la tuberculose ravageait Montréal à un rythme disproportionné par rapport aux autres villes canadiennes, entraînant plus de 1000 décès par an, et il est possible que la famille de Ho Sang Kee ait été victime de cette « peste blanche » dévastatrice. Après cette période, le nom de Ho Sang Kee disparaît de la presse et des archives publiques. Il travaille sans doute dans l’Ouest à cette époque, et ses enfants sont pris en charge par la famille Wilson à Québec. Dans les années 1930, Ho Sang Kee vit avec sa fille Avis, mariée à James Lee. Ho Sang Kee meurt en 1949 et est enterré au Cimetière Urgel Bourgie à Montréal.

Ho Sang Kee se méfie de plus en plus des journalistes au fur et à mesure des années 1890, probablement en grande partie à cause des gros titres sensationnels et des articles publiés à son sujet sur tout le continent. Un journal de la Colombie-Britannique le qualifie à la fois de « roi de la contrebande de l’Est » et de « prince des contrebandiers » dans le même article, et une grande partie de la presse nord-américaine à son sujet est tout aussi peu recommandable. Peut-être que cette frénésie médiatique autour de sa vie l’a incité à se retirer de la scène publique. Cependant, il figure souvent et de façon favorable dans les articles montréalais d’Edith Eaton des années 1890, et il a manifestement un large cercle composé de sa famille, de ses amis, d’associés et de connections, tant au Canada qu’aux États-Unis. Le Boston Globe fait état d’un banquet de mariage à Boston en l’honneur de M. et Mme Sang Kee tenu quelques jours seulement avant leur banquet à Montréal, et note que « toute l’élite de Chinatown » et « de nombreux Américains éminents, y compris des représentants du gouvernement à Burlington et Boston » étaient invités. Eaton décrit un flot de messages de félicitations pour Ho Sang Kee affluant à Montréal de la part « d’amis de Boston et de New York » lorsque son fils George est né en 1895.

Malgré les mystères actuels qui demeurent non résolus sur sa vie, il est clair que Sang Kee a vécu au cœur d’une communauté transnationale de Nord-Américains chinois et a aidé à l’hébergement de milliers d’hommes chinois dans sa pension de Montréal à une époque tumultueuse où le Canada et les États-Unis s’efforçaient de les faire disparaître par voie législative.

Sources 來源

“A Chinaman Investigating.” The Ottawa Journal. 29 Oct 1892: 1. https://www.newspapers.com/image/44403868

“A Chinese Child Born at the Hotel on Lagauchetiere Street.” The Montreal Star. 30 Sept 1895: 1. https://www.newspapers.com/image/740892614

“A Chinese Joint Pulled.” The Montreal Gazette. 06 Sept 1892: 5. https://www.newspapers.com/image/419299191

“A Dead Chinee and Thirty-Five Living Chinamen at Windsor Station – The Quong Hing Boarding House.” The Montreal Star. 07 Nov 1893: https://www.newspapers.com/image/740887964

“An Advance Step in the White Plague War.” The Montreal Star. 9 Sept 1908: 4. https://www.newspapers.com/image/739462624

“A Street Directory of Montreal.” Collection d’annuaires Lovell de Montréal et sa région, 1898-1899: 233. https://collections.banq.qc.ca/ark:/52327/3653002.

“A Street Directory of Montreal. M-Z.” Collection d’annuaires Lovell de Montréal et sa région, 1908-1909: 498. https://collections.banq.qc.ca/ark:/52327/3653002.

“Bidden to the Feast.” The Montreal Gazette. 14 Dec. 1893: 3. https://www.newspapers.com/image/419330059

“Birds’ Nest Soup for Bride.” The Boston Globe. 16 Dec 1893: 10. https://www.newspapers.com/image/430703721

“Briefs.” The Montreal Gazette. 16 May 1896: 3. https://www.newspapers.com/image/419335209

“Chinese Immigrants.” The Montreal Gazette. 19 Jan 1898: 3. https://www.newspapers.com/image/420313408

“Chinese Returning Home.” The Montreal Gazette. 6 Dec 1893. https://www.newspapers.com/image/419329057

“Collapse of a Sensation.” The Montreal Star. 14 Jul 1894: 4. https://www.newspapers.com/image/740878348

“‘Completion of the Moon.’ Sang Kee’s Baby’s Head Shaved.” The Montreal Star. 23 Oct 1895: 6. https://www.newspapers.com/image/740893254

“Death of Chinese Boy.” The Montreal Gazette. 5 Mar 1908: 3. https://www.newspapers.com/image/420311267

“First Chinese Woman.” The Montreal Gazette. 2 Jul 1908: 3. https://www.newspapers.com/image/420762169

“J. B. Picken Retires.” The Montreal Gazette. 22 Feb 1913: 9. https://www.newspapers.com/image/419700765

“Jew Guey.” Genealogy / Immigration & Citizenship / Immigrants from China, 1885 to 1952, Government of Canada. http://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=immfrochi&id=17198&lang=eng

“Our Mongolian Visitors.” The Montreal Gazette. 19 Sept 1893: 2. https://www.newspapers.com/image/419326582

“Prince of Smugglers”. Victoria Times Colonist. 16 Jul 1894: 1. https://www.newspapers.com/image/508283565

“Sang Kee and Miss Chu See.” The Montreal Star. 20 Dec 1893: 8. https://www.newspapers.com/image/740890294

“Sang Kee’s Hotel Raided.” The Montreal Star. 25 Apr 1896: 16. https://www.newspapers.com/image/740885352

“Sang Kee’s Humor.” The Boston Globe. 6 Aug 1894: 8. https://www.newspapers.com/image/430675774

“Scharf’s Failure to Prove His Chinese Smuggling Charges Places Him in an Awkward Position.” The Montreal Star. 3 Aug 1894: 6. https://www.newspapers.com/image/740879608

“The Chinese Colony. A Visit to Sang Kee’s Big Boarding House.” The Montreal Star. 15 Jun 1895: 8. https://www.newspapers.com/image/740718942

“The Chinese Land of Promise.” The Montreal Star. 23 Jun 1894: 8. www.newspapers.com/image/740900828