Edith Eaton (Sui Sin Far), 1865-1914 and the Birth of Asian North American Writing

Contents: English | 漢語 | Français | Sources 來源 | Images 圖片

English

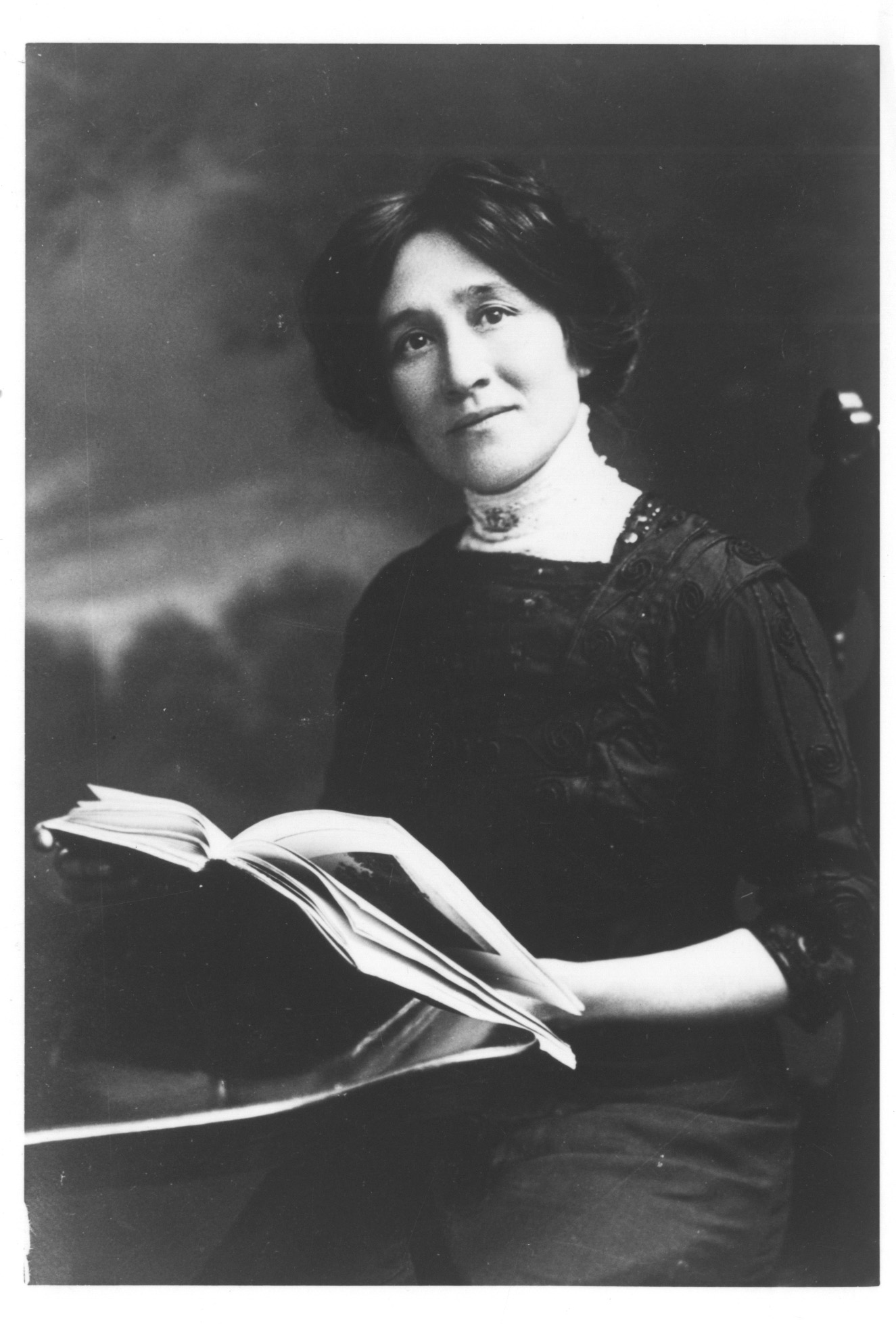

Journalist - Fiction Writer - Community Spokesperson

By Mary Chapman and Meghna Chatterjee

Edith Maude Eaton was born in 1865 in a silk-weaving town in Northern England. A few months after her birth, her Chinese-born mother Achuen “Grace” Amoy and her white British-born father, Edward Eaton, moved with Edith and her brother Charles Edward to New York, where Edward established a drug and dye business. But the growing family returned to England in 1868. When the Eatons ventured to North America again in 1872, this time with five children under eight in tow, they settled in Montreal’s Hochelaga neighbourhood.

Edith and her siblings were probably the only half-Chinese in Montreal in the 1870s and 1880s, when the Chinese community numbered only a handful of men who operated laundries. Edith recalls her brother and herself being called racial slurs. Anti-Chinese sentiment, particularly after the completion of the Canadian transcontinental railroad, led several of Edith’s siblings to “pass” as Japanese, Spanish or Mexican.

But Edith, after she and her mother were encouraged by a clergyman to visit two Chinese women new to Montreal, began to openly identify as Chinese. She began to write anonymous articles about Montreal’s small but growing diasporic Chinese community for the Montreal Witness and Montreal Star. As a half-Chinese “lady reporter,” Edith had privileged access to the intimate lives of Chinese merchants and their families: their babies’ births, their ceremonies, their marriages, and their social lives, all of which later inspired her Chinatown fiction. Edith also wrote numerous letters to the Editors defending Chinese immigrants from racist government policy such as the Chinese Head Tax policy.

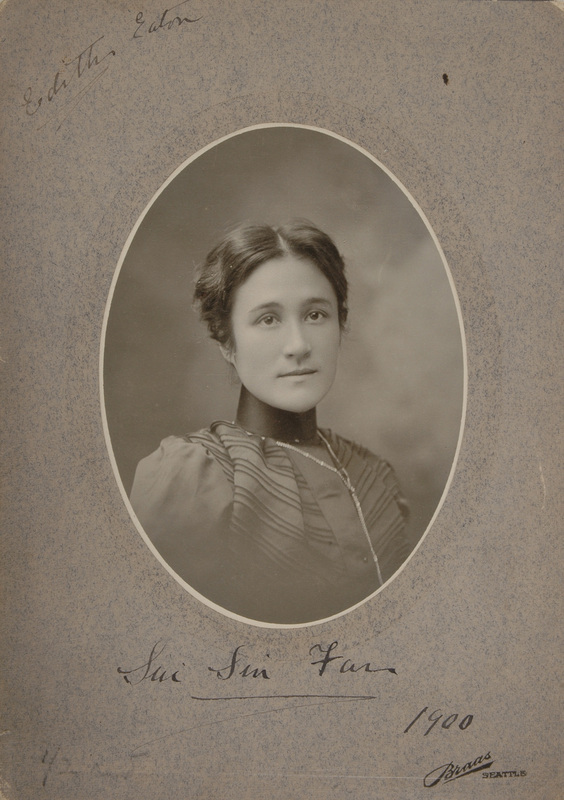

When she emigrated to the US in 1898, Edith assumed the pen name “Sui Sin Far,” which means “Chinese sacred lily,” and began to publish stories about the diasporic Chinese communities of San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Seattle, in local periodicals such as the Seattle Post-Intelligencer and The Westerner; missionary magazines such as The Interior, the Christian Evangelist, and the Sabbath Recorder; children’s magazines such as Children’s and Little Folks; and women’s magazines such as Ladies’ Home Journal, Delineator, Designer, Good Housekeeping, Housekeeper, Holland’s, and American Motherhood. She also wrote advertising copy for railway companies and a fifteen-installment travelogue from the perspective of a male Chinese merchant “Wing Sing” for the Los Angeles Express. By 1909, her work had been published in nearly 40 popular US and Canadian magazines and newspapers.

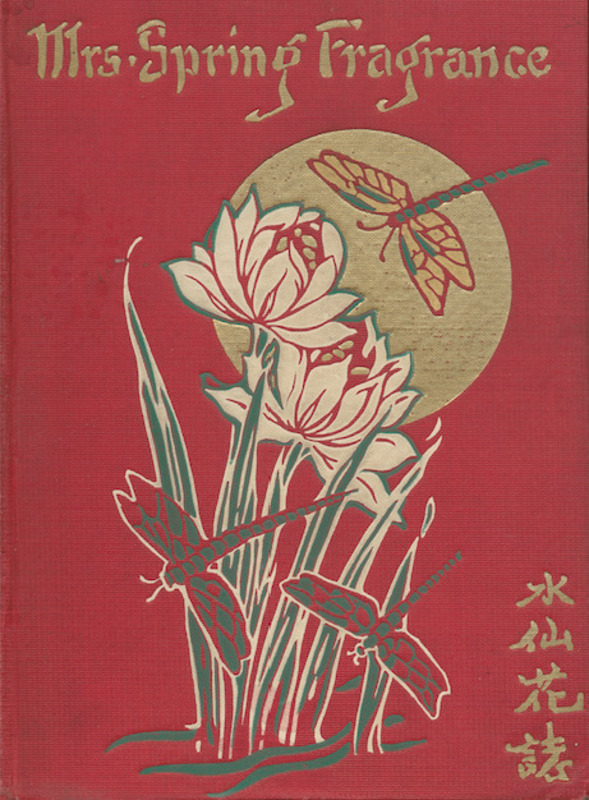

After 1910, Edith had achieved enough success through her writing that she no longer had to supplement her income with stenographic work. She moved to Boston where she devoted the next two years to assembling the manuscript for Mrs. Spring Fragrance, her first and only book, which collected seventeen short stories for adults and twenty “Tales of Chinese Children”, most of which had already appeared in U.S. magazines. When Edith died two years later in Montreal of heart disease, she left a manuscript behind that has never been found.

漢語

Edith Eaton/ 水仙花 (1865-1914) 與亞洲北美寫作的誕生

記者 - 小說作家 - 社區發言人

作者 Mary Chapman 與 Meghna Chatterjee

Edith Maude Eaton 於1865年出生在英國北部的一個絲織城鎮。在她出生幾個月後,她的中國出生的母親 Achuen (Grace) Amoy 和她的英國出生的白人父親Edward Eaton與Edith和她的兄弟Charles Edward一起搬到了紐約,Edward在那裡建立了一家藥品和染料公司。但這個不斷壯大的家庭於1868年返回英國。1872年,Eaton一家再次前往北美,這次帶著五個不到八歲的孩子,他們定居在蒙特利爾的Hochelaga社區。

在1870年代和1880年代的蒙特利爾,Edith和她的兄弟姐妹可能是唯一的半華裔,當時華人社區僅有少數經營洗衣店的男性。Edith回憶起她和她的兄弟經常被稱為種族歧視詞語。特別是在加拿大橫貫大陸鐵路建成後,反華情緒加劇,導致Edith的幾個兄弟姐妹假裝成日本人、西班牙人或墨西哥人。

然而,在一名牧師的鼓勵下,Edith和她的母親去看望兩名剛到蒙特婁的中國婦女後,開始公開承認自己是中國人。她開始匿名為《蒙特利爾見證報》和《蒙特利爾之星》撰寫有關蒙特利爾小而日益壯大的華人社區的文章。作為一名半華裔的“女記者”,Edith能夠特權地接觸到華人商人及其家人的私人生活:他們的嬰兒誕生、儀式、婚禮和社交生活,這些後來都啟發了她的唐人街小說。Edith還給編輯寫了許多封信,捍衛華人移民免受種族主義政策的影響,例如華人頭稅政策。

當她於1898年移民美國時,Edith採用筆名“水仙花”(Sui Sin Far),意思是“中國的神聖百合”,並開始在舊金山、洛杉磯和西雅圖等地的當地期刊上發表有關華人移民社區的故事,這些期刊包括《西雅圖郵訊智報》和《西部人》;宣教雜誌,如《內外雜誌》、《基督教傳道者》和《安息記錄》;兒童雜誌,如《兒童雜誌》和《小朋友們》;以及女性雜誌,如《女士之家》、《時裝師》、《設計師》、《好家政》、《家政專家》、《荷蘭》和《美國母親》。她還為鐵路公司寫廣告詞文案,並以一名男性華人商人Wing Sing的視角,為《洛杉磯快報》寫了一篇長達十五篇的遊記。到1909年,她的作品已經在近40家美國和加拿大的流行雜誌和報紙上發表。

1910年後,Edith通過她的寫作取得了足夠的成功,不再需要以速記工作來補充收入。她搬到波士頓,在那裡她花了接下來的兩年時間編纂《Mrs. Spring Fragrance》(圖2)的手稿,這是她唯一的一本書,收錄了十七個成人短篇小說和二十個“中國兒童故事”,其中大部分已經在美國的雜誌上刊登過。兩年後,當Edith因心臟疾病在蒙特利爾去世時,她留下了一份從未被找到的手稿。

Français

Edith Eaton / Sui Sin Far (1865-1914) et la naissance de l’écriture nord-américaine asiatique

Journaliste - Écrivaine - Porte-parole Communautaire

Par Mary Chapman et Meghna Chatterjee

Edith Maude Eaton est née en 1865 dans une ville de tissage de soie du nord de l’Angleterre. Quelques mois après sa naissance, sa mère d’origine chinoise Achuen «Grace» Amoy et son père blanc d’origine britannique, Edward Eaton, déménagent avec Edith et son frère Charles Edward à New York, où Edward établit une entreprise de médicaments et de teinture. Mais la famille, qui s’agrandit, retourne en Angleterre en 1868. Lorsque les Eaton s’aventurent de nouveau en Amérique du Nord en 1872, cette fois avec cinq enfants de moins de huit ans, ils s’installent dans le quartier montréalais d’Hochelaga.

Edith et ses frères et sœurs étaient probablement les seuls habitants de Montréal qui étaient à moitié chinois dans les années 1870 et 1880, car la communauté chinoise ne comptait qu’une poignée d’hommes qui travaillaient dans des blanchisseries. Edith se souvient qu’elle et son frère ont été victimes d’insultes raciales. Le sentiment anti-chinois, en particulier après l’achèvement du chemin de fer transcontinental canadien, a conduit plusieurs frères et sœurs d’Edith à se faire passer pour des Japonais, des Espagnols ou des Mexicains. Mais après leur rencontre avec un homme d’église qui les encouragea à rendre visite à deux femmes chinoises fraîchement arrivées à Montréal, Edith et sa mère commencèrent à revendiquer leurs origines chinoises publiquement.

Edith se met à écrire des articles anonymes sur la communauté chinoise diasporique de Montréal, petite mais grandissante, pour le Montreal Witness et le Montreal Star. Grâce à son statut de journaliste à moitié chinoise, elle avait un accès privilégié à la vie intime des marchands chinois et de leurs familles : la naissance de leurs bébés, leurs cérémonies, leurs mariages et leur vie sociale. Tous ces éléments inspirèrent plus tard sa fiction sur Chinatown, le quartier chinois.

Edith a également écrit de nombreuses lettres aux rédacteurs en chef pour défendre les immigrants chinois contre les politiques gouvernementales racistes telles que la taxe d’entrée imposée aux immigrants chinois. Lorsqu’elle émigre aux États-Unis en 1898, Edith prend le nom de plume « Sui Sin Far », qui signifie « lys sacré chinois », et commence à publier des histoires sur les communautés diasporiques chinoises de San Francisco, Los Angeles et Seattle. Elle les publie dans des périodiques locaux tels que le Seattle Post-Intelligencer et The Western; des magazines missionnaires comme The Interior, le Christian Evangelist et le Sabbath Recorder ; les magazines pour enfants comme Children’s et Little Folks; et des magazines féminins tels que Ladies’ Home Journal, Delineator, Designer, Good Housekeeping, Housekeeper, Holland’s et American Motherhood. Elle écrit également des textes publicitaires pour des compagnies de chemin de fer et un récit de voyage en quinze épisodes du point de vue d’un marchand chinois «Wing Sing» pour le Los Angeles Express. En 1909, son travail avait été publié dans près de 40 magazines et journaux populaires américains et canadiens.

Après 1910, Edith obtient suffisamment de succès grâce à ses écrits pour ne plus avoir à compléter ses revenus par un travail sténographique. Elle s’installe à Boston où elle consacre les deux années suivantes à assembler le manuscrit de Mrs. Spring Fragrance, son premier et unique livre, qui rassemble dix-sept nouvelles pour adultes et vingt « Tales of Chinese Children » (« Contes pour enfants chinois »), dont la plupart avaient été déja publiés dans des magazines américains. Lorsqu’ Edith meurt deux ans plus tard à Montréal d’une maladie cardiaque, elle laisse derrière elle un manuscrit qui n’a jamais été retrouvé.

Sources 來源

Chapman, Mary. Becoming Sui Sin Far: Early Fiction, Journalism, and Travel Writing by Edith Maude Eaton. McGill-Queen’s UP, 2016.

Sui Sin Far. Mrs. Spring Fragrance. (Chicago: McClurg, 1912).